Thursday, April 2, 2020

Sunday, February 23, 2020

Stoddard's 1897 Grand Canyon Visit

Below is the verbatim full account of John L. Stoddard's 1897 Trip to The Grand Canyon as excerpted from his book "John L. Stoddard's Lectures Volume 10.

Source: http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/15526

STARTING FOR THE GRAND CAÑON.

THE DRIVE THROUGH THE PINES.

THE SAN FRANCISCO MOUNTAIN.

THE LUNCH STATION.

HANCE'S CAMP.

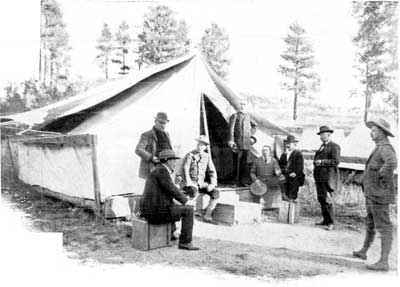

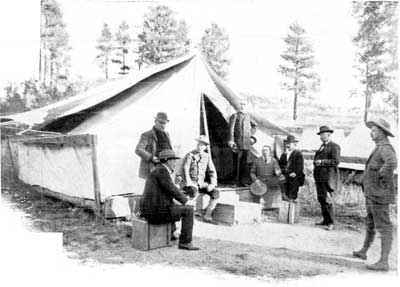

OUR TENT AT HANCE'S CAMP.

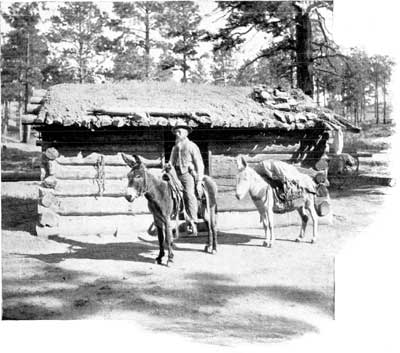

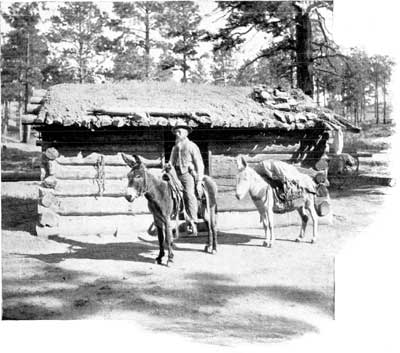

OLD HANCE.

THE FIRST VIEW.

THE EARTH-GULF OF ARIZONA.

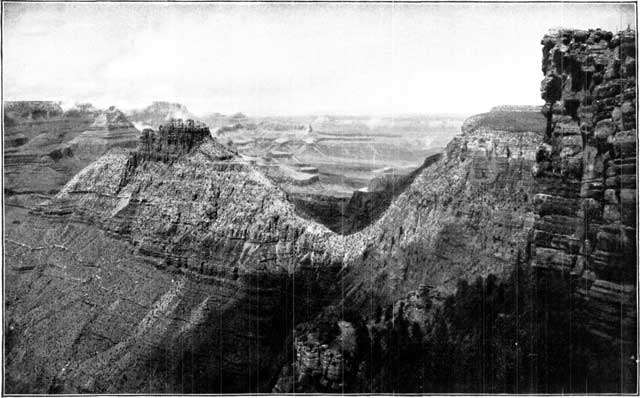

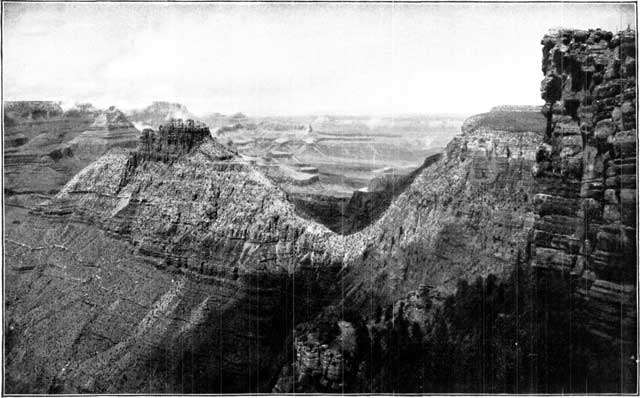

A PORTION OF THE GULF.

"A VAST, INCOMPARABLE VOID."

A SECTION OF THE LABYRINTH.

MOUNT AYER.

SOME OF THE CAÑON TEMPLES.

SIVA'S TEMPLE.

NEAR THE TEMPLE OF SET.

HANCE'S TRAIL, LOOKING UP.

MIST IN THE CAÑON.

A STUPENDOUS PANORAMA.

A TANGLED SKEIN OF CAÑONS.

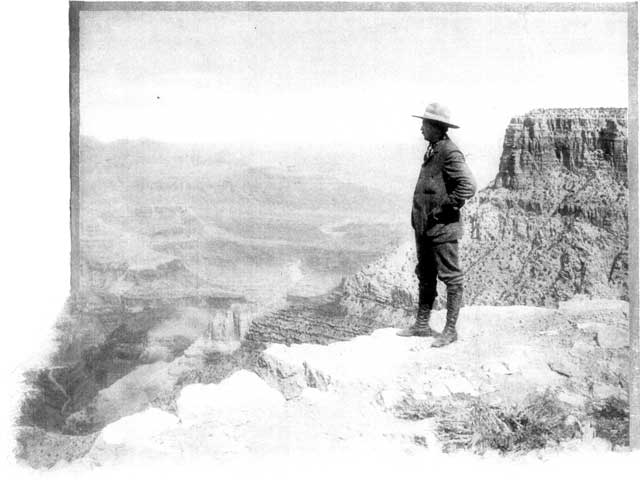

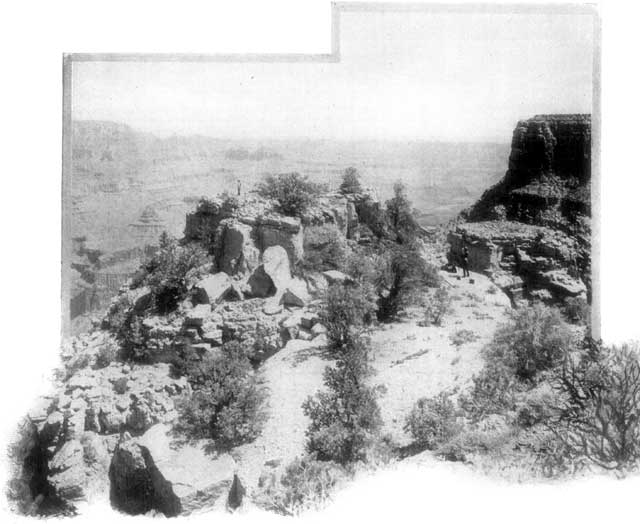

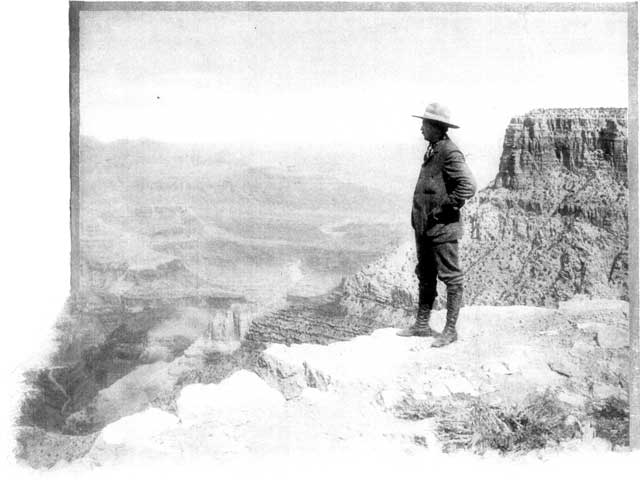

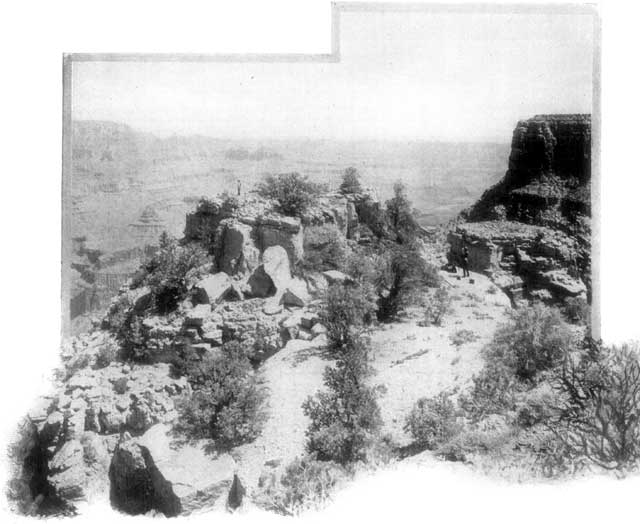

ON THE BRINK.

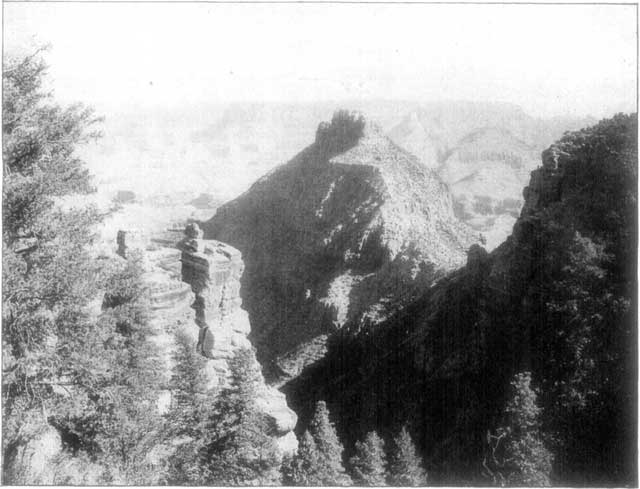

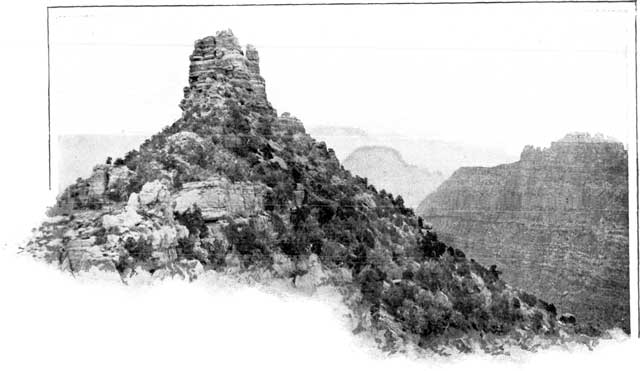

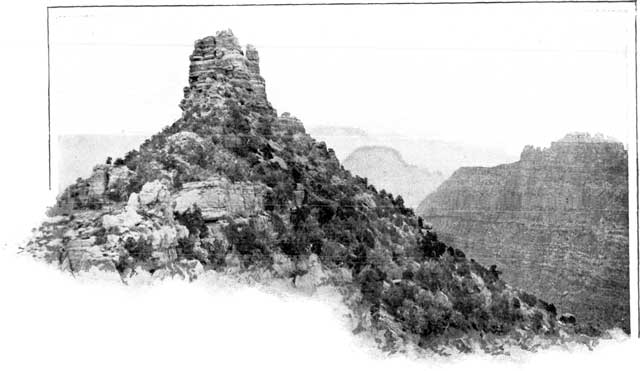

RIPLEY'S BUTTE.

A BIT OF THE RIVER.

ON HANCE'S TRAIL.

A VISION OF SUBLIMITY.

STARTING DOWN THE TRAIL.

A YAWNING CHASM.

OBLIGED TO WALK.

A CABIN ON THE TRAIL.

A HALT.

AT THE BOTTOM.

TAKING LUNCH NEAR THE RIVER.

BESIDE THE COLORADO.

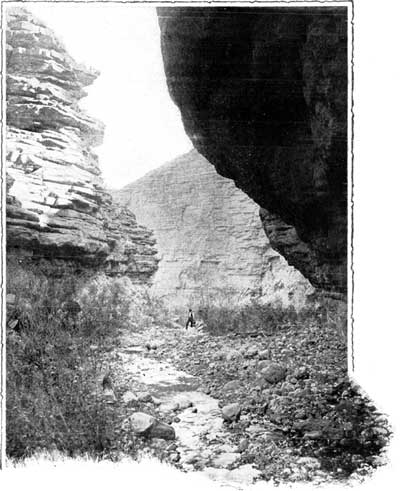

MONSTER CLIFFS, AND A NOTCH IN THE CAÑON WALL.

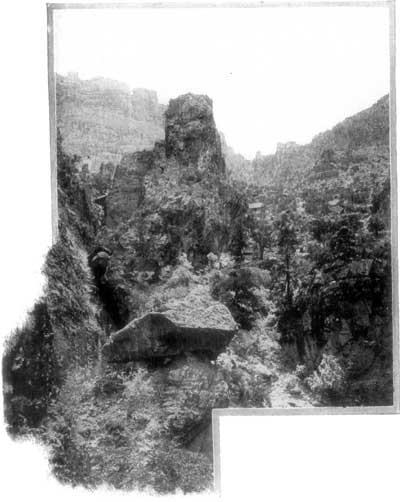

MILES OF INTRA-CAÑONS.

Source: http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/15526

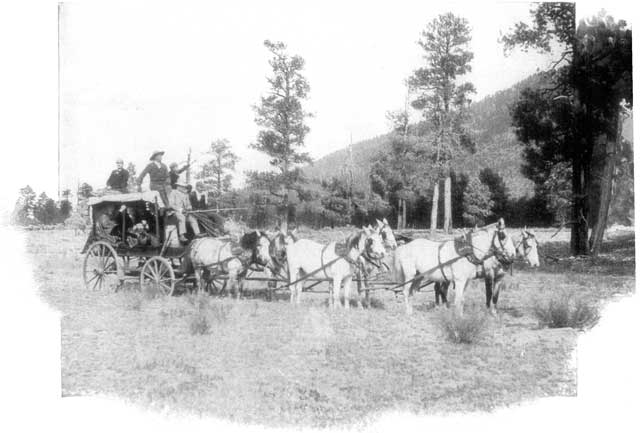

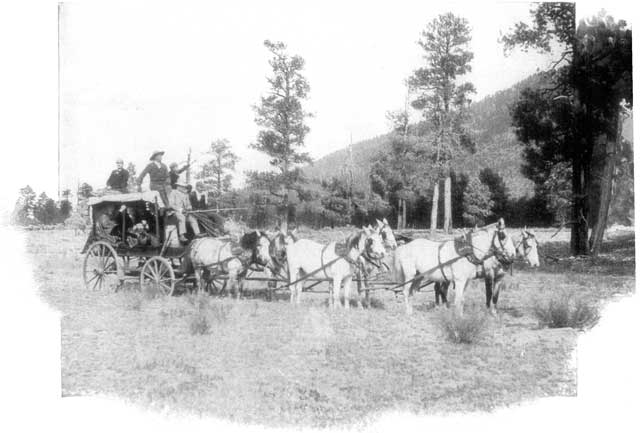

STARTING FOR THE GRAND CAÑON.

One glorious September morning, leaving our train at Flagstaff, we started in stage-coaches for a drive of sixty-five miles to the Grand Cañon. I had looked forward to this drive with some misgiving, dreading the heat of the sun, and the dust and sand which I had supposed we should encounter; but to my astonishment and delight it was a thoroughly enjoyable experience. It was only eleven hours in duration, and not only was most of the route level, but two-thirds of it lay through a section of beautifully rolling land, diversified with open glades and thousands upon thousands of tall pines and cedars entirely free from undergrowth. It is no exaggeration to say that we drove that day for miles at a time over a road carpeted with pine needles. The truth is, Arizona, though usually considered a treeless and rainless country, possesses some remarkable exceptions; and the region near Flagstaff not only abounds in stately pines, but is at certain seasons visited by rainstorms which keep it fresh and beautiful. During our stay at the Grand Cañon we had a shower every night; the atmosphere was marvelously pure, and aromatic with the odors of a million pines; and so exhilarating was exercise in the open air, that however arduous it might be, we never felt inconvenienced by fatigue, and mere existence gave us joy. Decidedly, then, it will not do to condemn the whole of Arizona because of the heat of its arid, southern plains; for the northern portion of the state is a plateau, with an elevation of from five thousand to seven thousand feet. Hence, as it is not latitude, so much as altitude, that gives us healthful, pleasing temperature, in parts of Arizona the climate is delightful during the entire year.

THE DRIVE THROUGH THE PINES.

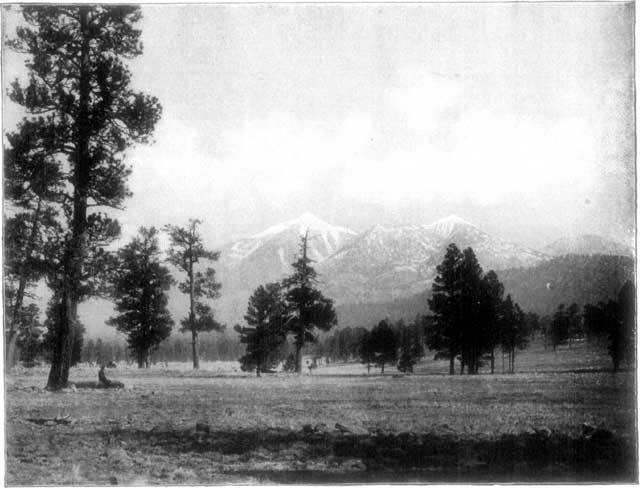

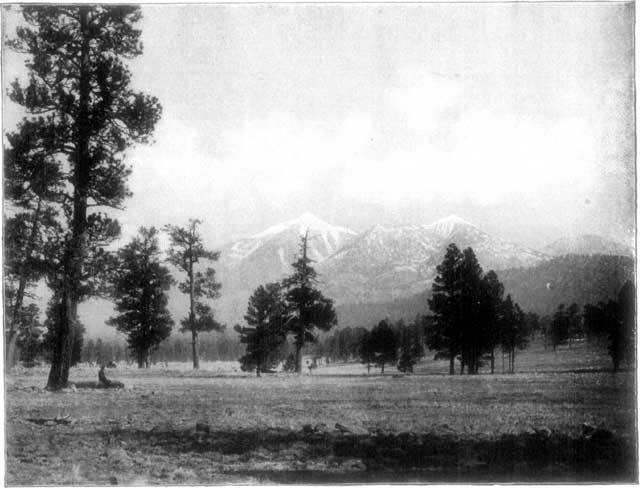

THE SAN FRANCISCO MOUNTAIN.

A portion of this stage-coach journey led us over the flank of the great San Francisco Mountain. The isolated position, striking similarity, and almost uniform altitude of its four peaks, rising nearly thirteen thousand feet above the sea, have long made them famous. Moreover, they are memorable for having cast a lurid light upon the development of this portion of our planet. Cold, calm, and harmless though they now appear, the time has been when they contained a molten mass which needed but a throb of Earth's uneasy heart to light the heavens with an angry glare, and cover the adjoining plains with floods of fire. Lava has often poured from their destructive cones, and can be traced thence over a distance of thirty miles; proving that they once served as vents for the volcanic force which the thin crust of earth was vainly striving to confine. But their activity is apparently ended. The voices with which they formerly shouted to one another in the joy of devastation have been silenced. Conquered at last, their fires smolder now beneath a barrier too firm to yield, and their huge forms appear like funeral monuments reared to the memory of the power buried at their base. Another fascinating sight upon this drive was that of the Painted Desert whose variously colored streaks of sand, succeeding one another to the rim of the horizon, made the vast area seem paved with bands of onyx, agate, and carnelian.

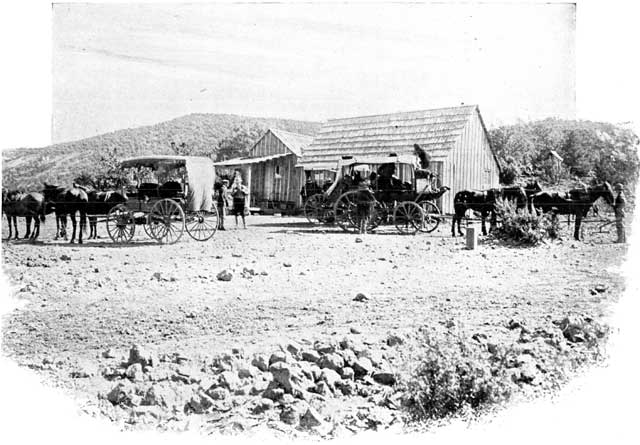

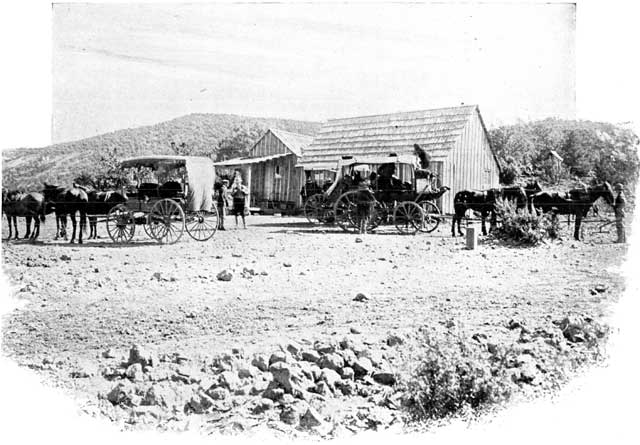

THE LUNCH STATION.

About the hour of noon we reached a lunch-station at which the stages, going to and from the Cañon, meet and pass. The structure itself is rather primitive; but a good meal is served to tourists at this wayside halting-place, and since our appetites had been sharpened by the long ride and tonic-giving air, it seemed to us the most delicious of repasts. The principal object of one of the members of our party, in making the journey described in these pages, was to determine the advisability of building a railroad from Flagstaff to the Cañon. Whether this will be done eventually is not, however, a matter of vital interest to travelers, since the country traversed can easily be made an almost ideal coaching-route; and with good stages, frequent relays of horses, and a well-appointed lunch-station, a journey thus accomplished would be preferable to a trip by rail.

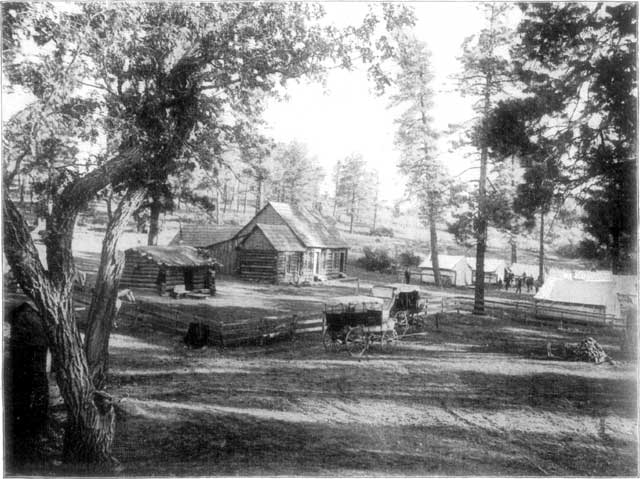

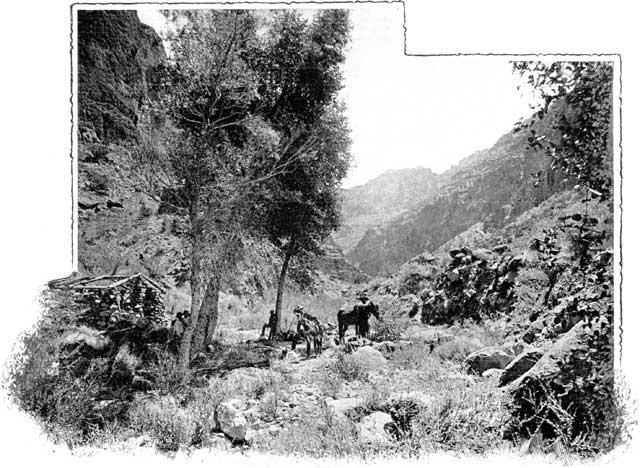

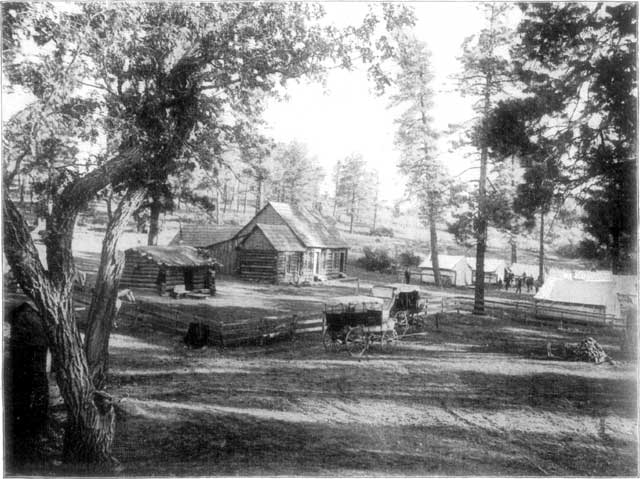

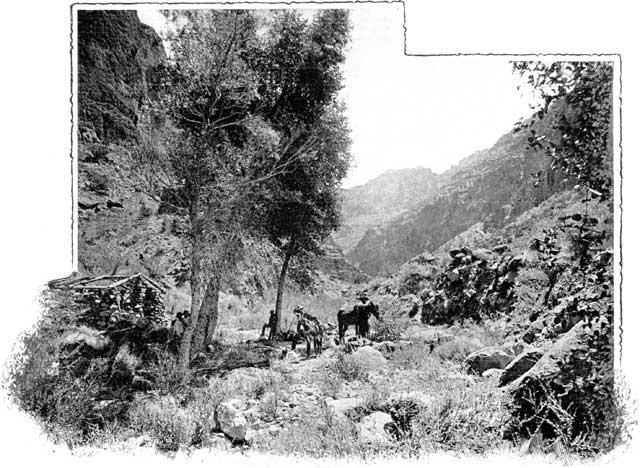

HANCE'S CAMP.

OUR TENT AT HANCE'S CAMP.

Night had already come when we arrived at our destination, known as Hance's Camp, near the border of the Cañon. As we drove up to it, the situation seemed enchanting in its peace and beauty; for it is located in a grove of noble pines, through which the moon that night looked down in full-orbed splendor, paving the turf with inlaid ebony and silver, and laying a mantle of white velvet on the tents in which we were to sleep. Hance's log cabin serves as a kitchen and dining-room for travelers, and a few guests can even find lodging there; but, until a hotel is built, the principal dormitories must be the tents, which are provided with wooden floors and furnished with tables, chairs, and comfortable beds. This kind of accommodation, however, although excellent for travelers in robust health, is not sufficiently luxurious to attract many tourists. The evident necessity of the place is a commodious, well-kept inn, situated a few hundred feet to the rear of Hance's Camp, on the very edge of the Cañon. If such a hotel, built on a spot commanding the incomparable view, were properly advertised and well-managed, I firmly believe that thousands of people would come here every year, on their way to or from the Pacific coast—not wishing or expecting it to be a place of fashion, but seeking it as a point where, close beside a park of pines, seven thousand feet above the level of the sea, one of the greatest marvels of the world can be enjoyed, in all the different phases it presents at morning, noon, and night, in sunshine, moonlight, and in storm.

OLD HANCE.

THE FIRST VIEW.

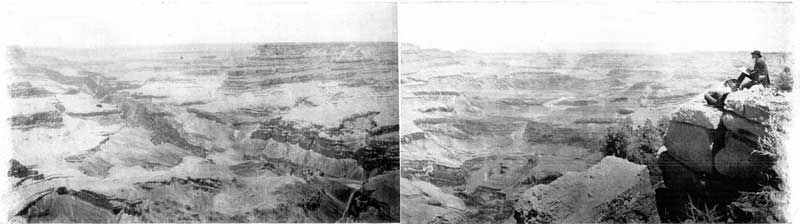

Early the next morning I eagerly climbed the little knoll at the foot of which our tents were located, for I well knew that from its summit I should see the Cañon. Many grand objects in the world are heralded by sound: the solemn music of Niagara, the roar of active geysers in the Yellowstone, the intermittent thunder of the sea upon a rocky coast, are all distinguishable at some distance; but over the Grand Cañon of the Colorado broods a solemn silence. No warning voice proclaims its close proximity; no partial view prepares us for its awful presence. We walk a few steps through the pine trees from the camp and suddenly find ourselves upon the Cañon's edge. Just before reaching it, I halted for a moment, as has always been my wont when approaching for the first time any natural or historic object that I have longed for years to look upon. Around me rose the stately pines; behind me was a simple stretch of rolling woodland; nothing betrayed the nearness of one of the greatest wonders of the world. Could it be possible that I was to be disappointed? At last I hurried through the intervening space, gave a quick look, and almost reeled. The globe itself seemed to have suddenly yawned asunder, leaving me trembling on the hither brink of two dissevered hemispheres. Vast as the bed of a vanished ocean, deep as Mount Washington, riven from its apex to its base, the grandest cañon on our planet lay glittering below me in the sunlight like a submerged continent, drowned by an ocean that had ebbed away. At my very feet, so near that I could have leaped at once into eternity, the earth was cleft to a depth of six thousand six hundred feet—not by a narrow gorge, like other cañons, but by an awful gulf within whose cavernous immensity the forests of the Adirondacks would appear like jackstraws, the Hudson Palisades would be an insignificant stratum, Niagara would be indiscernible, and cities could be tossed like pebbles.

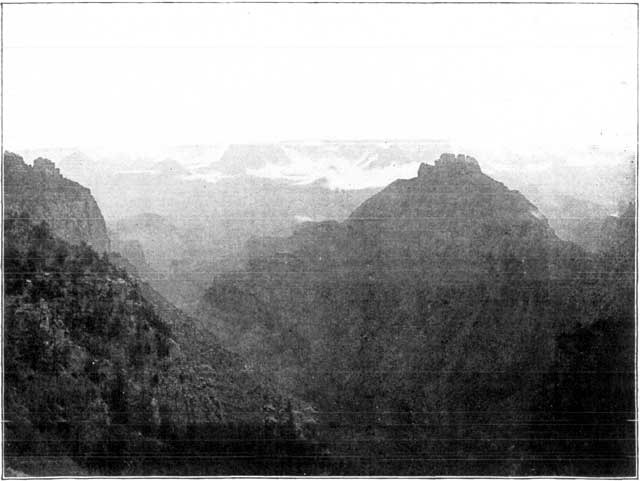

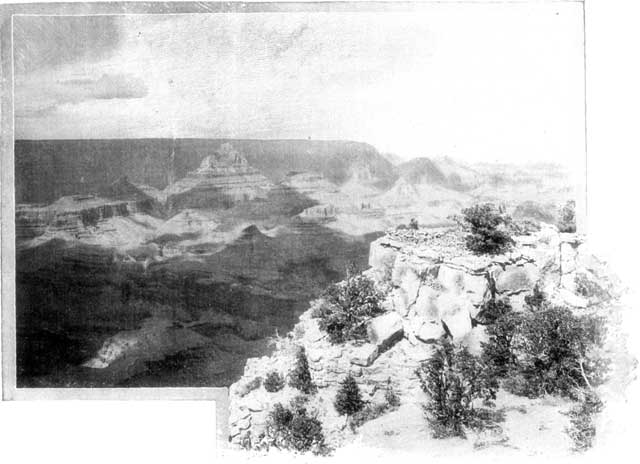

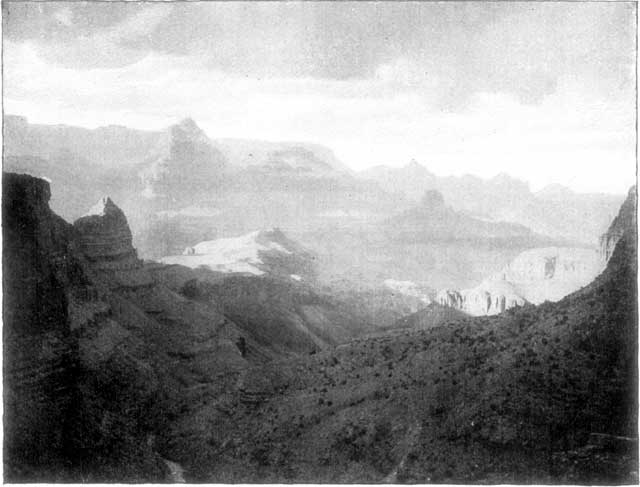

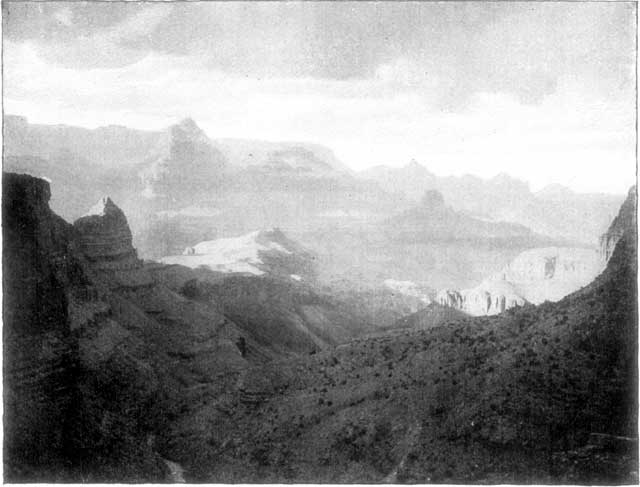

THE EARTH-GULF OF ARIZONA.

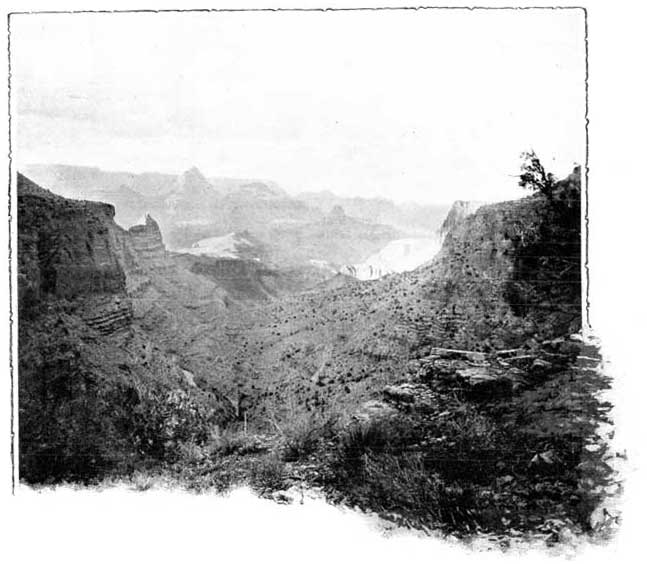

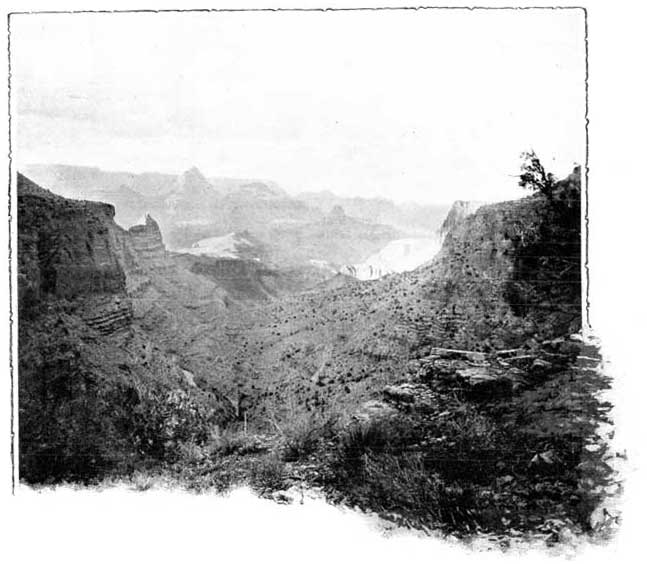

A PORTION OF THE GULF.

"A VAST, INCOMPARABLE VOID."

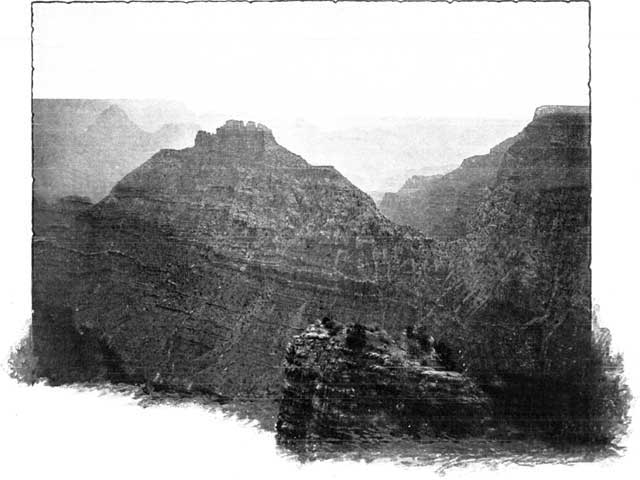

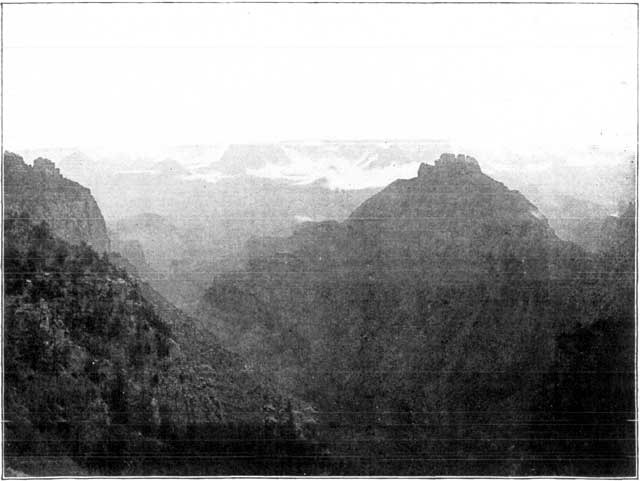

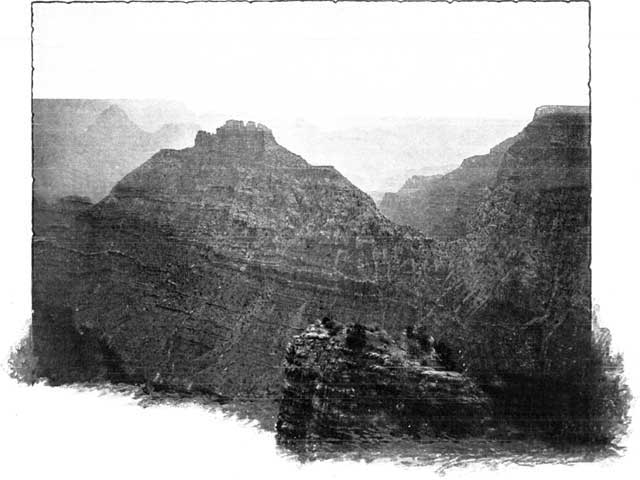

As brain grew steadier and vision clearer, I saw, directly opposite, the other side of the Cañon thirteen miles away. It was a mountain wall, a mile in height, extending to the right and left as far as the eye could reach; and since the cliff upon which I was standing was its counterpart, it seemed to me as if these parallel banks were once the shore-lines of a vanished sea. Between them lay a vast, incomparable void, two hundred miles in length, presenting an unbroken panorama to the east and west until the gaze could follow it no farther. Try to conceive what these dimensions mean by realizing that a strip of the State of Massachusetts, thirteen miles in width, and reaching from Boston to Albany, could be laid as a covering over this Cañon, from one end to the other; and that if the entire range of the White Mountains were flung into it, the monstrous pit would still remain comparatively empty! Even now it is by no means without contents; for, as I gazed with awe and wonder into its colossal area, I seemed to be looking down upon a colored relief-map of the mountain systems of the continent. It is not strictly one cañon, but a labyrinth of cañons, in many of which the whole Yosemite could be packed away and lost. Thus one of them, the Marble Cañon, is of itself more than three thousand feet deep and sixty-six miles long. In every direction I beheld below me a tangled skein of mountain ranges, thousands of feet in height, which the Grand Cañon's walls enclosed, as if it were a huge sarcophagus, holding the skeleton of an infant world. It is evident, therefore, that all the other cañons of our globe are, in comparison with this, what pygmies are to a giant, and that the name Grand Cañon, which is often used to designate some relatively insignificant ravine, should be in truth applied only to the stupendous earth-gulf of Arizona.

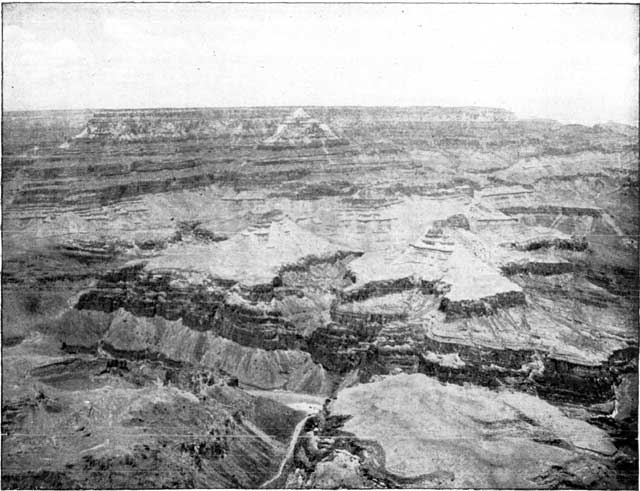

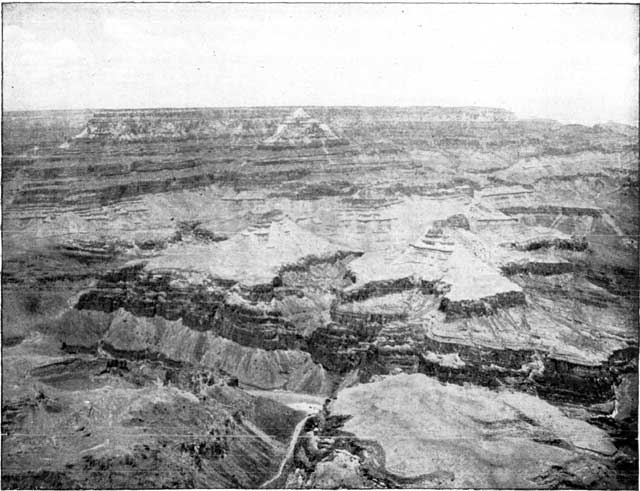

A SECTION OF THE LABYRINTH.

MOUNT AYER.

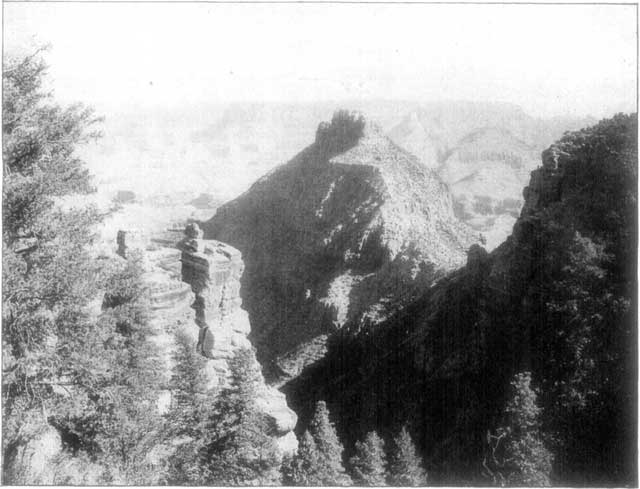

At length, I began to try to separate and identify some of these formations. Directly in the foreground, a savage looking mountain reared its splintered head from the abyss, and stood defiantly confronting me, six thousand feet above the Cañon's floor. Though practically inaccessible to the average tourist, this has been climbed, and is named Mount Ayer, after Mrs. Edward Ayer, the first woman who ever descended into the Cañon to the river's edge. Beyond this, other mountains rise from the gulf, many of which resemble the Step Pyramid at Sakhara, one of the oldest of the royal sepulchres beside the Nile. But so immeasurably vaster are the pyramids of this Cañon than any work of man, that had the tombs of the Pharaohs been placed beside them, I could not have discovered them without a field-glass. Some of these grand constructions stand alone, while others are in pairs; and many of them resemble Oriental temples, buttressed with terraces a mile or two in length, and approached by steps a hundred feet in height. Around these, too, are many smaller mountainous formations, crude and unfinished in appearance, like shrines commenced and then abandoned by the Cañon's Architect. Most of us are but children of a larger growth, and love to interpret Nature, as if she reared her mountains, painted her sunsets, cut her cañons, and poured forth her cataracts solely for our instruction and enjoyment. So, when we gaze on forms like these, shaped like gigantic temples, obelisks, and altars fashioned by man's hands, we try to see behind them something personal, and even name them after Hindu, Grecian, and Egyptian gods, as if those deities made them their abodes. Thus, one of these shrines was called by the artist, Thomas Moran, the Temple of Set; three others are dedicated respectively to Siva, Vishnu, and Vulcan; while on the apex of a mighty altar, still unnamed, a twisted rock-formation, several hundred feet in height, suggests a flame, eternally preserved by unseen hands, ascending to an unknown god.

SOME OF THE CAÑON TEMPLES.

SIVA'S TEMPLE.

It is difficult to realize the magnitude of these objects, so deceptive are distances and dimensions in the transparent atmosphere of Arizona. Siva's Temple, for example, stands upon a platform four or five miles square, from which rise domes and pinnacles a thousand feet in height. Some of their summits call to mind immense sarcophagi of jasper or of porphyry, as if they were the burial-places of dead deities, and the Grand Cañon a Necropolis for pagan gods. Yet, though the greater part of the population of the world could be assembled here, one sees no worshipers, save an occasional devotee of Nature, standing on the Cañon's rim, lost in astonishment and hushed in awe. These temples were, however, never intended for a human priesthood. A man beside them is a pygmy. His voice here would be little more effective than the chirping of an insect. The God-appointed celebrant, in the cathedrals of this Cañon, must be Nature. Her voice alone can rouse the echoes of these mountains into deafening peals of thunder. Her metaphors are drawn from an experience of ages. Her prayers are silent, rapturous communings with the Infinite. Her hymns of praise are the glad songs of birds; her requiems are the meanings of the pines; her symphonies the solemn roaring of the winds. "Sermons in stone" abound at every turn; and if, as the poet has affirmed, "An undevout astronomer is mad," with still more truth can it be said that those are blind who in this wonderful environment look not "through Nature up to Nature's God." These wrecks of Tempest and of Time are finger-posts that point the thoughts of mortals to eternal heights; and we find cause for hope in the fact that, even in a place like this, Man is superior to Nature; for he interprets it, he finds in it the thoughts of God, and reads them after Him.

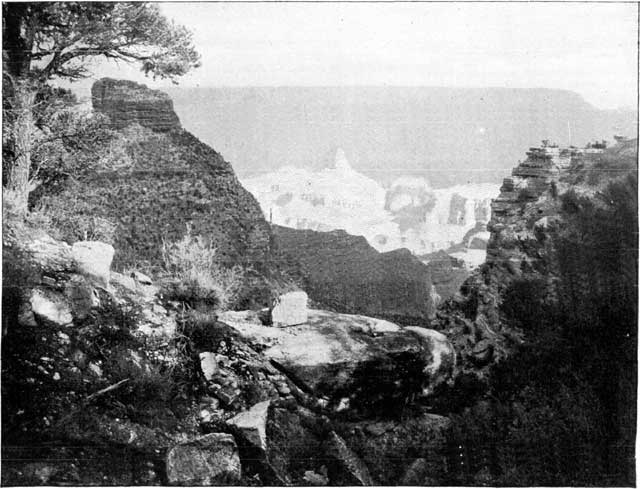

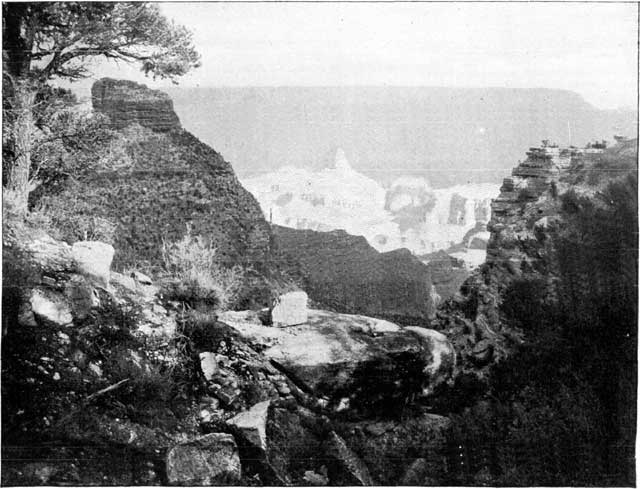

NEAR THE TEMPLE OF SET.

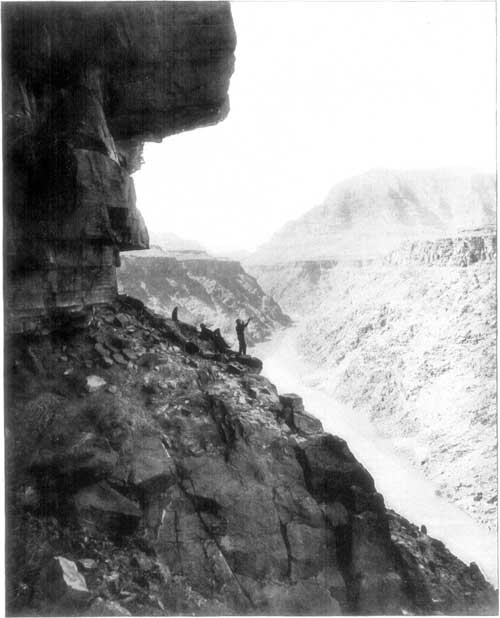

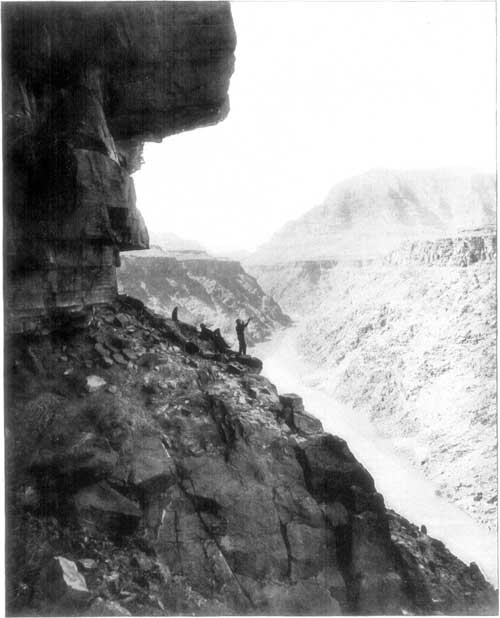

HANCE'S TRAIL, LOOKING UP.

The coloring of the Grand Cañon is no less extraordinary than its forms. Nature has saved this chasm from being a terrific scene of desolation by glorifying all that it contains. Wall after wall, turret after turret, and mountain range after mountain range belted with tinted strata, succeed one another here like billows petrified in glowing colors. These hues are not as brilliant and astonishing in their variety as are the colors of the Yellowstone Cañon, but their subdued and sombre tones are perfectly suited to the awe-inspiring place which they adorn. The prominent tints are yellow, red, maroon, and a dull purple, as if the glory of unnumbered sunsets, fading from these rugged cliffs, had been in part imprisoned here. Yet, somehow, specimens of these colored rocks lose all their brilliancy and beauty when removed from their environment, like sea-shells from the beach; a verification of the sentiment so beautifully expressed in the lines of Emerson:

"I wiped away the weeds and foam,

I fetched my sea-born treasures home;

But the poor, unsightly, noisome things

Had left their beauty on the shore,

With the sun and the sand and the wild uproar."

MIST IN THE CAÑON.

To stand upon the edge of this stupendous gorge, as it receives its earliest greeting from the god of day, is to enjoy in a moment compensation for long years of ordinary uneventful life. When I beheld the scene, a little before daybreak, a lake of soft, white clouds was floating round the summits of the Cañon mountains, hiding the huge crevasse beneath, as a light coverlet of snow conceals a chasm in an Alpine glacier. I looked with awe upon this misty curtain of the morn, for it appeared to me symbolic of the grander curtain of the past which shuts out from our view the awful struggles of the elements enacted here when the grand gulf was being formed. At length, however, as the light increased, this thin, diaphanous covering was mysteriously withdrawn, and when the sun's disk rose above the horizon, the huge facades of the temples which looked eastward grew immediately rosy with the dawn; westward, projecting cliffs sketched on the opposite sides of the ravines, in dark blue silhouettes, the evanescent forms of castles, battlements, and turrets from which some shreds of white mist waved like banners of capitulation; stupendous moats beneath them were still black with shadow; while clouds filled many of the minor cañons, like vapors rising from enormous cauldrons. Gradually, as the solar couriers forced a passage into the narrow gullies, and drove the remnant of night's army from its hiding-places, innumerable shades of purple, yellow, red, and brown appeared, varying according to the composition of the mountains, and the enormous void was gradually filled to the brim with a luminous haze, which one could fancy was the smoke of incense from its countless altars. A similar, and even more impressive, scene is visible here in the late afternoon, when all the western battlements in their turn grow resplendent, while the eastern walls submit to an eclipse; till, finally, a gray pall drops upon the lingering bloom of day, the pageant fades, the huge sarcophagi are mantled in their shrouds, the gorgeous colors which have blazed so sumptuously through the day grow pale and vanish, the altar fires turn to ashes, the mighty temples draw their veils and seem deserted by both gods and men, and the stupendous panorama awaits, beneath the canopy of night, the glory of another dawn.

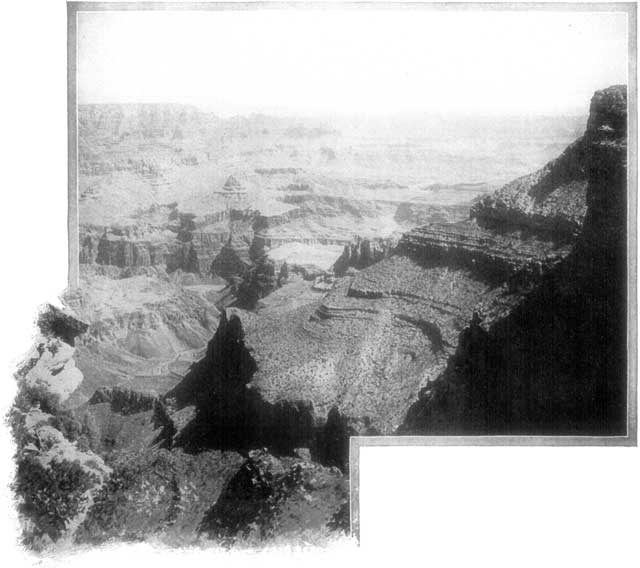

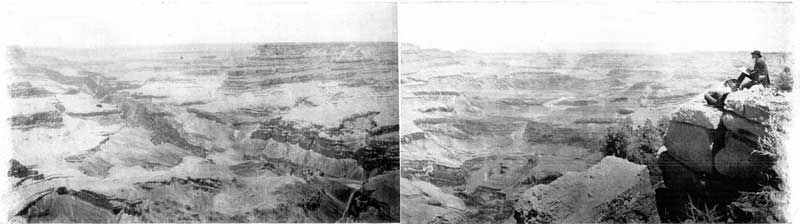

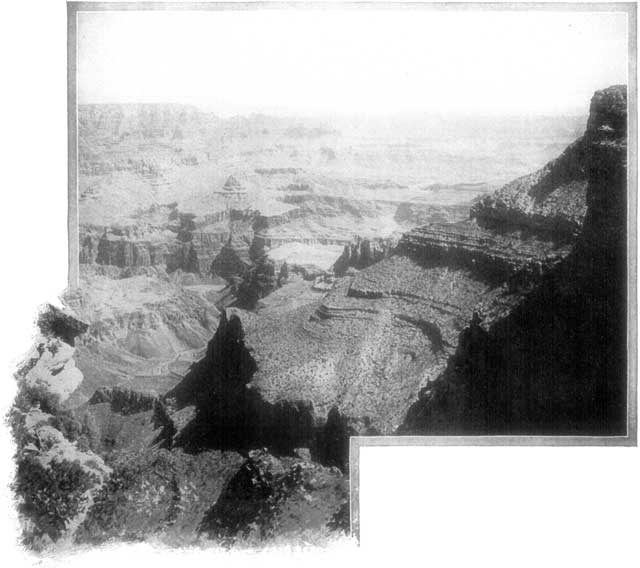

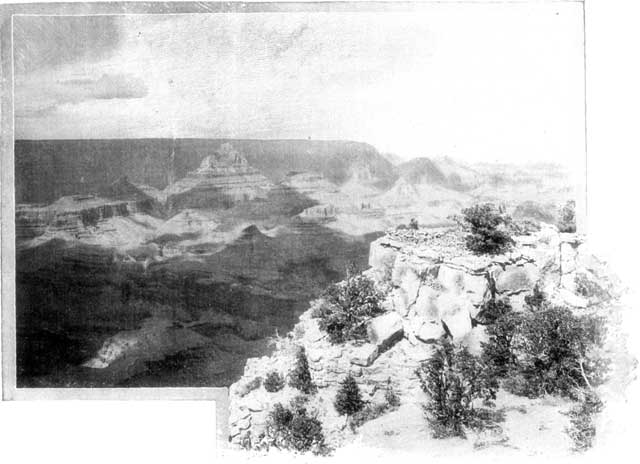

A STUPENDOUS PANORAMA.

A TANGLED SKEIN OF CAÑONS.

It was my memorable privilege to see, one afternoon, a thunder storm below me here. A monstrous cloud-wall, like a huge gray veil, came traveling up the Cañon, and we could watch the lightning strike the buttes and domes ten or twelve miles away, while the loud peals of thunder, broken by crags and multiplied by echoes, rolled toward us through the darkening gulf at steadily decreasing intervals. Sometimes two flashes at a time ran quivering through the air and launched their bolts upon the mountain shrines, as though their altars, having been erected for idolatrous worship, were doomed to be annihilated. Occasionally, through an opening in the clouds, the sun would suddenly light up the summit of a mountain, or flash a path of gold through a ravine; and I shall never forget the curious sensation of seeing far beneath me bright sunshine in one cañon and a violent storm in another. At last, a rainbow cast its radiant bridge across the entire space, and we beheld the tempest disappear like a troop of cavalry in a cloud of dust beneath that iridescent arch, beyond whose curving spectrum all the temples stood forth, still intact in their sublimity.

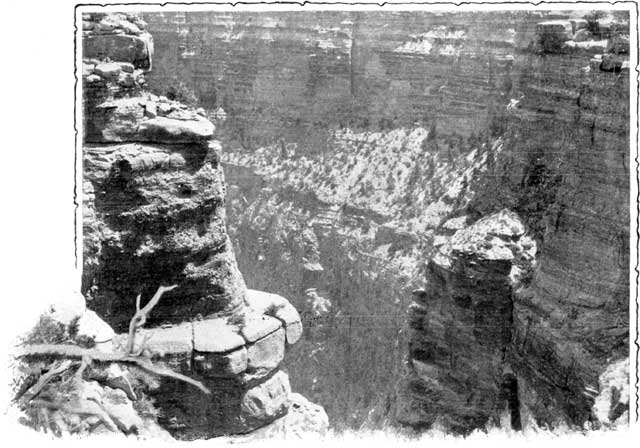

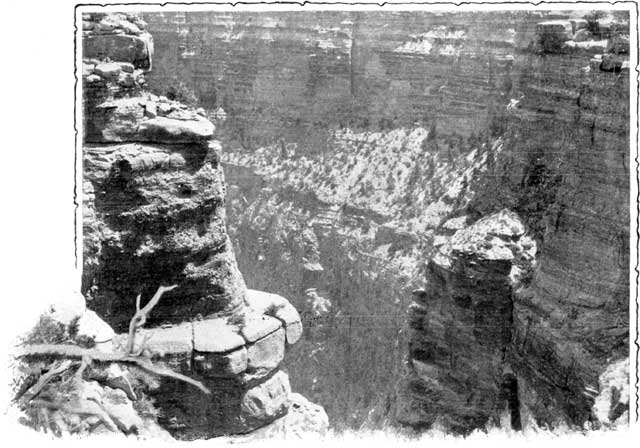

ON THE BRINK.

At certain points along the Cañon, promontories jut out into the abyss, like headlands which in former times projected into an ocean that has disappeared. Hence, riding along the brink, as one may do for miles, we looked repeatedly into many lateral fissures, from fifteen hundred to three thousand feet in depth. All these, however, like gigantic fingers, pointed downward to the centre of the Cañon, where, five miles away, and at a level more than six thousand feet below the brink on which we stood, extended a long, glittering trail. This, where the sunlight struck it, gleamed like an outstretched band of gold. It was the sinuous Colorado, yellow as the Tiber.

RIPLEY'S BUTTE.

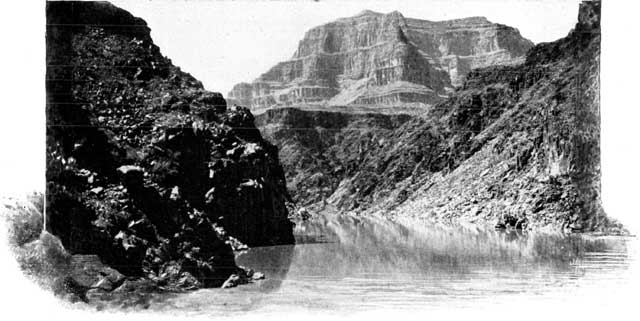

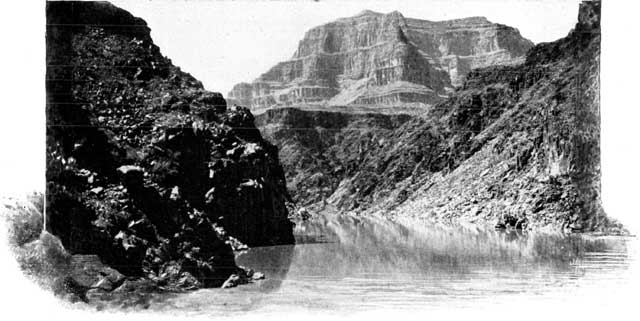

A BIT OF THE RIVER.

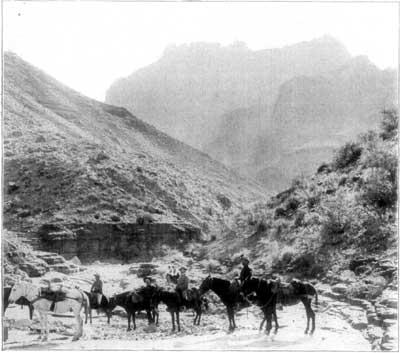

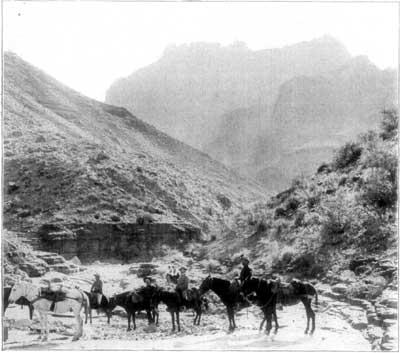

ON HANCE'S TRAIL.

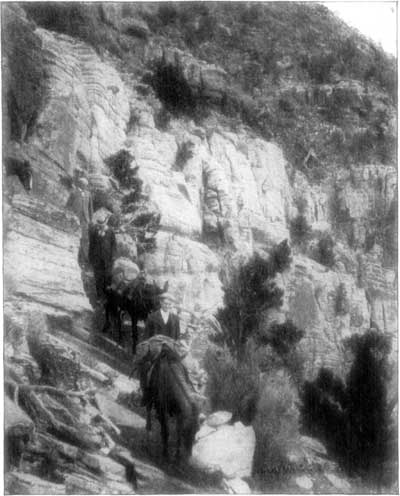

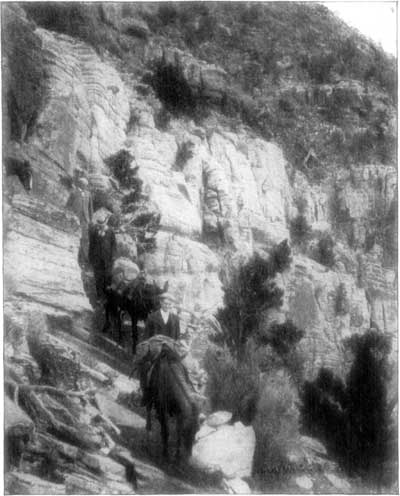

One day of our stay here was devoted to making the descent to this river. It is an undertaking compared with which the crossing of the Gemmi on a mule is child's play. Fortunately, however, the arduous trip is not absolutely necessary for an appreciation of the immensity and grandeur of the scenery. On the contrary, one gains a really better idea of these by riding along the brink, and looking down at various points on the sublime expanse. Nevertheless, a descent into the Cañon is essential for a proper estimate of its details, and one can never realize the enormity of certain cliffs and the extent of certain valleys, till he has crawled like a maimed insect at their base and looked thence upward to the narrowed sky. Yet such an investigation of the Cañon is, after all, merely like going down from a balloon into a great city to examine one of its myriad streets, since any gorge we may select for our descending path is but a tiny section of a labyrinth. That which is unique and incomparable here is the view from the brink; and when the promised hotel is built upon the border of the Cañon, visitors will be content to remain for days at their windows or on the piazzas, feasting their souls upon a scene always sublime and sometimes terrible.

A VISION OF SUBLIMITY.

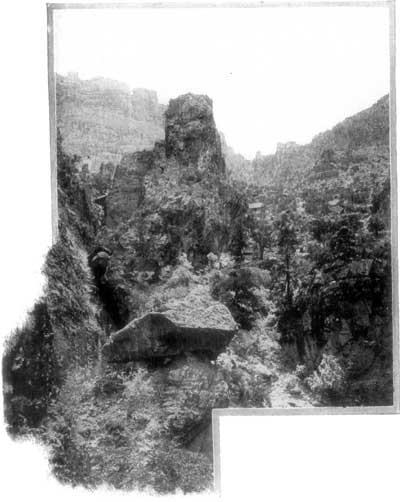

Nevertheless, desirous of exploring a specimen of these chasms (as we often select for minute examination a single painting out of an entire picture gallery) we made the descent to the Colorado by means of a crooked scratch upon a mountain side, which one might fancy had been blazed by a zigzag flash of lightning. As it requires four hours to wriggle down this path, and an equal amount of time to wriggle up, I spent the greater part of a day on what a comrade humorously styled the "quarter-deck of a mule." A square, legitimate seat in the saddle was usually impossible, so steep was the incline; and hence, when going down, I braced my feet and lay back on the haunches of the beast, and, in coming up, had to lean forward and clutch the pommel, to keep from sliding off, as a human avalanche, on the head of the next in line. In many places, however, riding was impossible, and we were compelled to scramble over the rocks on foot. The effect of hours of this exercise on muscles unaccustomed to such surprises may be imagined; yet, owing to the wonderfully restorative air of Arizona, the next day after this, the severest physical exertion I had ever known, I did not feel the slightest bad result, and was as fresh as ever. That there is an element of danger in this trip cannot be doubted. At times the little trail, on which two mules could not possibly have passed each other, skirts a precipice where the least misstep would hurl the traveler to destruction; and every turn of the zigzag path is so sharp that first the head and then the tail of the mule inevitably projects above the abyss, and wig-wags to the mule below. Moreover, though not a vestige of a parapet consoles the dizzy rider, in several places the animal simply puts its feet together and toboggans down the smooth face of a slanting rock, bringing up at the bottom with a jerk that makes the tourist see a large variety of constellations, and even causes his beast to belch forth an involuntary roar of disenchantment, or else to try to pulverize his immediate successor. In such a place as this Nature seems pitiless and cruel; and one is impressed with the reflection that a million lives might be crushed out in any section of this maze of gorges and not a feature of it would be changed. There is, however, a fascination in gambling with danger, when a desirable prize is to be gained. The stake we risk may be our lives, yet, when the chances are in our favor, we often love to match excitement against the possibility of death; and even at the end, when we are safe, a sigh sometimes escapes us, as when the curtain falls on an absorbing play.

STARTING DOWN THE TRAIL.

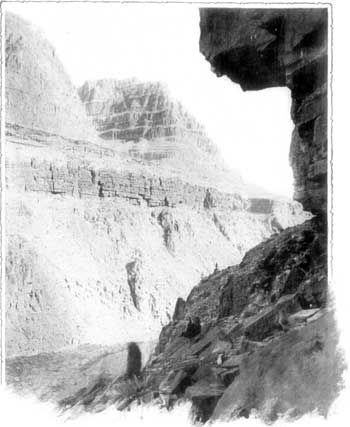

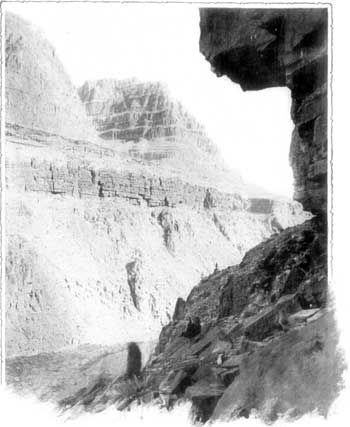

A YAWNING CHASM.

OBLIGED TO WALK.

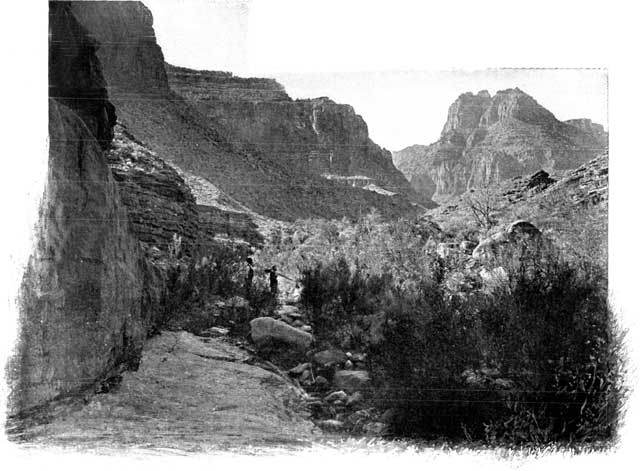

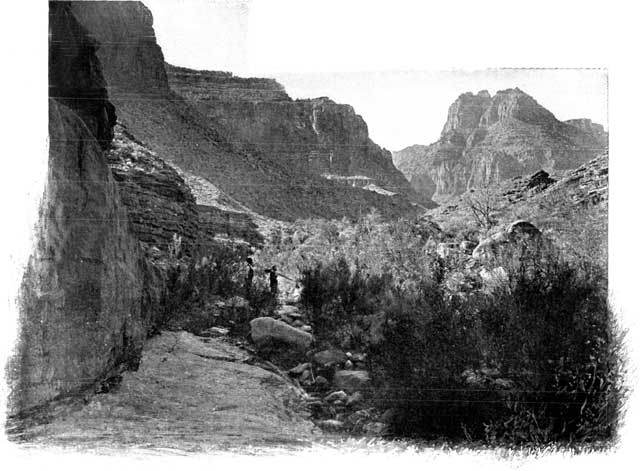

As we descended, it grew warmer, not only from the greater elevation of the sun at noon, but from the fact that in this sudden drop of six thousand feet we had passed through several zones of temperature. Snow, for example, may be covering the summits of the mountains in midwinter, while at the bottom of the Cañon are summer warmth and vernal flowers. When, after two or three hours of continuous descent, we looked back at our starting-point, it seemed incredible that we had ever stood upon the pinnacles that towered so far above us, and were apparently piercing the slowly moving clouds. The effect was that of looking up from the bottom of a gigantic well. Instinctively I asked myself if I should ever return to that distant upper world, and it gave me a memorable realization of my individual insignificance to stand in such a sunken solitude, and realize that the fissure I was exploring was only a single loop in a vast network of ravines, which, if extended in a straight line, would make a cañon seven hundred miles in length. It was with relief that we reached, at last, the terminus of the lateral ravine we had been following and at the very bottom of the Cañon rested on the bank of the Colorado. The river is a little freer here than elsewhere in its tortuous course, and for some hundred feet is less compressed by the grim granite cliffs which, usually, rise in smooth black walls hundreds of feet in almost vertical height, and for two hundred miles retain in their embrace the restless, foaming flood that has no other avenue of escape.

The navigation of this river by Major J.W. Powell, in 1869, was one of the most daring deeds of exploration ever achieved by man, and the thrilling story of his journey down the Colorado, for more than a thousand miles, and through the entire length of the Grand Cañon, is as exciting as the most sensational romance. Despite the remonstrances of friends and the warnings of friendly Indians, Major Powell, with a flotilla of four boats and nine men, started down the river, on May 24th, from Green River City, in Utah, and, on the 30th of August, had completed his stupendous task, with the loss of two boats and four men. Of the latter, one had deserted at an early date and escaped; but the remaining three, unwilling to brave any longer the terrors of the unknown Cañon, abandoned the expedition and tried to return through the desert, but were massacred by Indians. It is only when one stands beside a portion of this lonely river, and sees it shooting stealthily and swiftly from a rift in the Titanic cliffs and disappearing mysteriously between dark gates of granite, that he realizes what a heroic exploit the first navigation of this river was; for nothing had been known of its imprisoned course through this entanglement of chasms, or could be known, save by exploring it in boats, so difficult of access were, and are, the two or three points where it is possible for a human being to reach its perpendicular banks. Accordingly, when the valiant navigators sailed into these mysterious waters, they knew that there was almost every chance against the possibility of a boat's living in such a seething current, which is, at intervals, punctured with a multitude of tusk-like rocks, tortured into rapids, twisted into whirlpools, or broken by falls; while in the event of shipwreck they could hope for little save naked precipices to cling to for support. Moreover, after a heavy rain the Colorado often rises here fifty or sixty feet under the veritable cataracts of water which, for miles, stream directly down the perpendicular walls, and make of it a maddened torrent wilder than the rapids of Niagara. All honor, then, to Powell and his comrades who braved not alone the actual dangers thus described, but stood continually alert for unknown perils, which any bend in the swift, snake-like river might disclose, and which would make the gloomy groove through which they slipped a black-walled oubliette, or gate to Acheron.

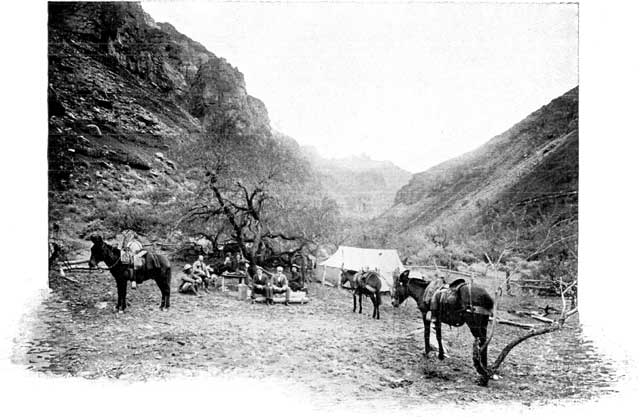

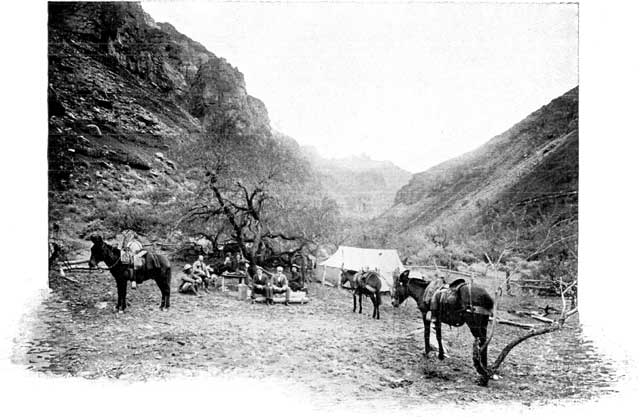

A CABIN ON THE TRAIL.

A HALT.

AT THE BOTTOM.

TAKING LUNCH NEAR THE RIVER.

BESIDE THE COLORADO.

If any river in the world should be regarded with superstitious reverence, it is the Colorado, for it represents to us, albeit in a diminished form, the element that has produced the miracle of the Arizona Cañon,—water. Far back in the distant Eocene Epoch of our planet's history, the Colorado was the outlet of an inland sea which drained off toward the Pacific, as the country of northwestern Arizona rose; and the Grand Cañon illustrates, on a stupendous scale, the system of erosion which, in a lesser degree, has deeply furrowed the entire region. At first one likes to think of the excavation of this awful chasm as the result of some tremendous cataclysm of Nature; but, in reality, it has all been done by water, assisted, no doubt, by the subtler action of the winds and storms in the disintegration of the monster cliffs, which, as they slowly crumbled into dust, were carried downward by the rains, and, finally, were borne off by the omnivorous river to the sea.

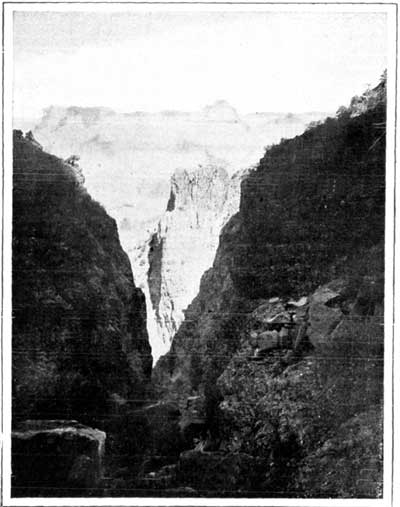

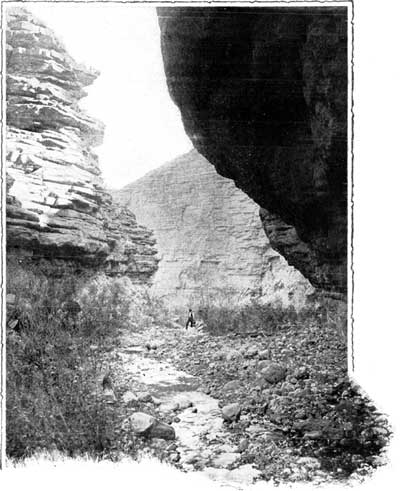

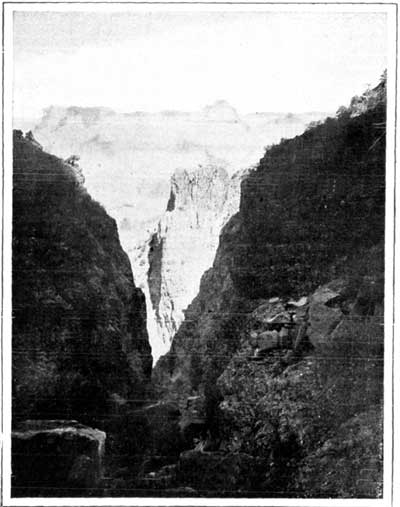

MONSTER CLIFFS, AND A NOTCH IN THE CAÑON WALL.

MILES OF INTRA-CAÑONS.

But though, at first, these agents do not seem as forceful and extraordinary as a single terrible catastrophe, the slow results thus gained are even more impressive. For what an appalling lapse of time must have been necessary to cut down and remove layers of sandstone, marble, and granite, thousands of feet in thickness; to carve the mighty shrines of Siva and of Vishnu, and to etch out these scores of interlacing cañons! To calculate it one must reckon a century for every turn of the hourglass. It is the story of a struggle maintained for ages between the solid and the fluid elements, in which at last the yielding water won a victory over adamant. It is an evidence, too, of Nature's patient methods; a triumph of the delicate over the strong, the liquid over the solid, the transitory over the enduring. At present, the softer material has been exhausted, and the rapacious river, shrunken in size, must satisfy itself by gnawing only the archaic granite which still curbs its course. Yet if this calculation overpowers us, what shall we say of the reflections awakened by the fact that all the limestone cliffs along the lofty edges of the Cañon are composed of fossils,—the skeletons of creatures that once lived here covered by an ocean, and that ten thousand feet of strata, which formerly towered above the present summits of the Cañon walls, have been eroded and swept downward to the sea! Hence, were the missing strata (all of which are found in regular sequence in the high plateaus of Utah) restored, this Cañon would be sixteen thousand feet in depth, and from its borders one could look down upon a mountain higher than Mont Blanc! To calculate the æons implied in the repeated elevations and subsidences which made this region what it is would be almost to comprehend eternity. In such a retrospect centuries crumble and disappear into the gulf of Time as pebbles into the Cañon of the Colorado.

On my last evening in the pine tree camp I left my tent and walked alone to the edge of the Grand Cañon. The night was white with the splendor of the moon. A shimmering lake of silvery vapor rolled its noiseless tide against the mountains, and laved the terraces of the Hindu shrines. The lunar radiance, falling into such profundity, was powerless to reveal the plexus of subordinate cañons, and even the temples glimmered through the upper air like wraiths of the huge forms which they reveal by day. Advancing cautiously to an isolated point upon the brink, I lay upon my face, and peered down into the spectral void. No voice of man, nor cry of bird, nor roar of beast resounded through those awful corridors of silence. Even thought had no existence in that sunken realm of chaos. I felt as if I were the sole survivor of the deluge. Only the melancholy murmur of the wind ascended from that sepulchre of centuries. It seemed the requiem for a vanished world.

Stoddard's Flagstaff Arrival

|

| John L. Stoddard's private rail car at Flagstaff |

We simply "had" to know when John L. Stoddard and his entourage arrived in Flagstaff. From our earlier post, we know it was sometime in September 1897 but we simply couldn't pin it down to a date or time. Then we got lucky.

We read Stoddard's narrative of the Flagstaff arrival. Here it is verbatim:

"It was late on the night succeeding our visit to Ácoma that we arrived at Flagstaff, and our entire party was asleep. Suddenly we were aroused by a prolonged shout and the discharge of half a dozen revolvers. Five minutes later there came a general fusillade of pistol shots, and near and distant cries were heard, in which our half-awakened faculties could distinguish only the words: "Hurry up!" "Call the crowd!" "Down the alley!" Then a gruff voice yelled just beneath my window: "Let her go," and instantly our locomotive gave a whistle so piercing and continuous that all the occupants of our car sprang from their couches, and met in a demoralized group of multicolored pajamas in the corridor. What was it? Had the train been held up? Were we attacked? No; both the whistle and the pistol shots were merely Flagstaff's mode of giving an alarm of fire. We hastily dressed and stepped out upon the platform. A block of buildings just opposite the station was on fire, and was evidently doomed; yet Flagstaff's citizens, whose forms, relieved against the lurid glow, looked like Comanche Indians in a war dance, fought the flames with stubborn fury. The sight of a successful conflagration always thrills me, partly with horror, partly with delight. Three hundred feet away, two buildings formed an ever-increasing pyramid of golden light. We could distinguish the thin streams of water thrown by two puny engines; but, in comparison with the great tongues of fire which they strove to conquer, they appeared like silver straws. Nothing could check the mad carousal of the sparks and flames, which danced, leaped, whirled, reversed, and intertwined, like demons waltzing with a company of witches on Walpurgis Night. A few adventurous men climbed to the roofs of the adjoining structures, and thence poured buckets of water on the angry holocaust; but, for all the good they thus accomplished, they might as well have spat upon the surging, writhing fire, which flashed up in their faces like exploding bombs, whenever portions of the buildings fell. Meantime huge clouds of dense smoke, scintillant with sparks, rolled heavenward from this miniature Vesuvius; the neighboring windows, as they caught the light, sparkled like monster jewels; two telegraph poles caught fire, and cut their slender forms and outstretched arms against the jet black sky, like gibbets made of gold. How fire and water serve us, when subdued as slaves; but, oh, how terribly they scourge us, if ever for a moment they can gain the mastery! Too interested to exchange a word, we watched the struggle and awaited the result. The fury of the fire seemed like the wild attack of Indians, inflamed with frenzy and fanaticism, sure to exhaust itself at last, but for the moment riotously triumphant. Gradually, however, through want of material on which to feed itself, the fiery demon drooped its shining crest, brandished its arms with lessening vigor, and seemed to writhe convulsively, as thrust after thrust from the silver spears of its assailants reached a vital spot. Finally, after hurling one last shower of firebrands, it sank back into darkness, and its hereditary enemy rushed in to drown each lingering spark of its reduced vitality."

Well, now, that's a mighty compelling piece of circumstantial evidence right there. We searched both of Platt Cline's Flagstaff history books with no luck. So, we kept using different search strings and finally pinned 'er down. They most likely arrived the night of September 13, 1897. After the party was all asleep, the above described fire broke out at 1:30 AM in the Grand Canyon Hotel.

How do we know? Check it out!

Source of Stoddard narrative and rail car photo:http://www.gutenberg.org/files/15526/15526-h/15526-h.htm#grand

Source of fire note: The Observatory, 1897https://books.google.com/books?id=m2xRAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA400&lpg=PA400&dq=september+1897+flagstaff+arizona+fire&source=bl&ots=MNzDQ3XWJF&sig=ACfU3U2UfiR1AuSJgl_fwt7lQSwuJV5mHA&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjd-K3Pl-jnAhUKv54KHR-5ARYQ6AEwGHoECAgQAQ#v=onepage&q=september%201897%20flagstaff%20arizona%20fire&f=false

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)